I think we should talk about it.

I used to be that annoying person in code review.

Not the “nit: rename variable” annoying.

More like: “why are we touching this at all?” and “what happens when this fails in prod?”

Over the years you learn a simple thing: most outages are not caused by idiots. They’re caused by normal people, doing reasonable things, under time pressure, inside systems that drift.

Code review was one of the few rituals that stopped drift.

And lately… It feels like that ritual is getting hollow.

Not in an obvious way. In a quiet way.

The moment I started noticing it

A PR comes in. The diff is big. Not “someone rewrote half the repo” big but big enough that your brain does that thing where it says: brother, not today.

You scroll.

You see code that looks… fine.

Readable, even. Clean formatting. Decent naming. Some tests.

You leave a comment or two, mostly on shape not substance.

CI is green. Someone else already approved. You approve too.

And then you move on.

That is the new normal in a lot of teams I speak to. And if I’m honest, in my own behaviour too when I’m tired.

Nobody is malicious here. Nobody is careless.

It’s just that the cost of producing code has fallen off a cliff, and the cost of understanding it hasn’t.

I asked myself: what is a code review supposed to do?

Forget GitHub. Forget “LGTM”. Forget templates.

Why does code review exist?

It exists to reduce the probability of future pain.

That’s it.

Review is not “find syntax errors”. Your compiler already does that.

Review is not “check formatting”. Your linter does that.

Review is not “make sure the author feels seen” (though that happens).

Review is: “are we about to ship something that will bite us?”

And historically, code review worked because the reviewer could, in a reasonable amount of time, build a mental model of the change.

That’s the part that’s breaking.

What changed: code got cheaper than attention

AI didn’t just make people write faster. It changed the shape of PRs.

- More files touched.

- More refactors “because why not”.

- More tests that look legitimate but weren’t written with intent.

- More code that the author themselves didn’t reason through line-by-line.

It’s not even a judgement. It’s just reality.

When code is expensive to write, you write less of it, and you tend to know why each piece exists.

When code is cheap to generate, you get a lot more “looks right” code.

And then the reviewer gets handed a diff that’s technically coherent… but cognitively expensive.

So reviewers do what humans do when faced with cognitive overload:

They skim.

They rubber-stamp.

They look for obvious smells and move on.

Again – not because they don’t care. Because the alternative is spending their entire week in code review.

The dangerous part: review still looks healthy

This is what scares me.

Because nothing has “broken” in the process. The PR still has approvals. Comments. Green checks. Merges.

So the org tells itself: we’re doing code review.

But the function of code review has changed.

It has gone from risk reduction to ceremony.

And ceremony is worse than no ceremony because it creates a false sense of safety.

What skimming misses (and why it matters)

When people skim, they still catch some things:

- obvious bugs

- typos

- broken tests

- “why is this variable named x”

But they miss the stuff that actually hurts you later:

1) Boundary mistakes

Auth edges. Permission checks. Input validation. Data exposure.

These bugs are usually boring-looking. They don’t scream.

2) “Works today, breaks later” logic

Retries. Timeouts. Partial failures. Out-of-order events.

Most of the production isn’t happy paths.

3) Slow architectural decay

The code is fine, but the system gets a little harder to change.

And then six months later you’re scared to touch it.

4) No blast radius thinking

What happens if this rolls out gradually?

What happens if it fails?

What’s the rollback story?

Most PRs don’t even mention this, and reviewers don’t demand it because… time.

The end result is not an immediate catastrophe.

It’s more subtle: you accumulate risk invisibly until one day you pay for it in a way that feels “sudden” but isn’t.

A conversation that made this feel real

I was discussing this with a Principal Engineer at Cloudflare (public thread, nothing private). He said something very blunt:

That line stuck with me because it’s a very human response to volume and not a culture problem.

So what now? “Just review harder” isn’t a plan.

Most advice here is useless because it’s moralising.

“Make PRs smaller.” Sure. Everyone agrees. Still doesn’t happen consistently.

“Spend more time reviewing.” Sure. Who’s giving you that time?

“Add more checklists.” Sure. Then people tick boxes faster.

If you accept the principle – that code review is supposed to reduce risk and then the question becomes:

How do we make sure the right parts of a change gets deep attention, even when the diff is huge and partially machine-written?

That’s the actual problem statement.

Not “how do we read more code”.

My Current Belief: Code Review has to become Guided, not Heroic

The old model of review was heroic: one human brain reads the diff and catches everything.

That model barely worked when PRs were smaller. It won’t work now.

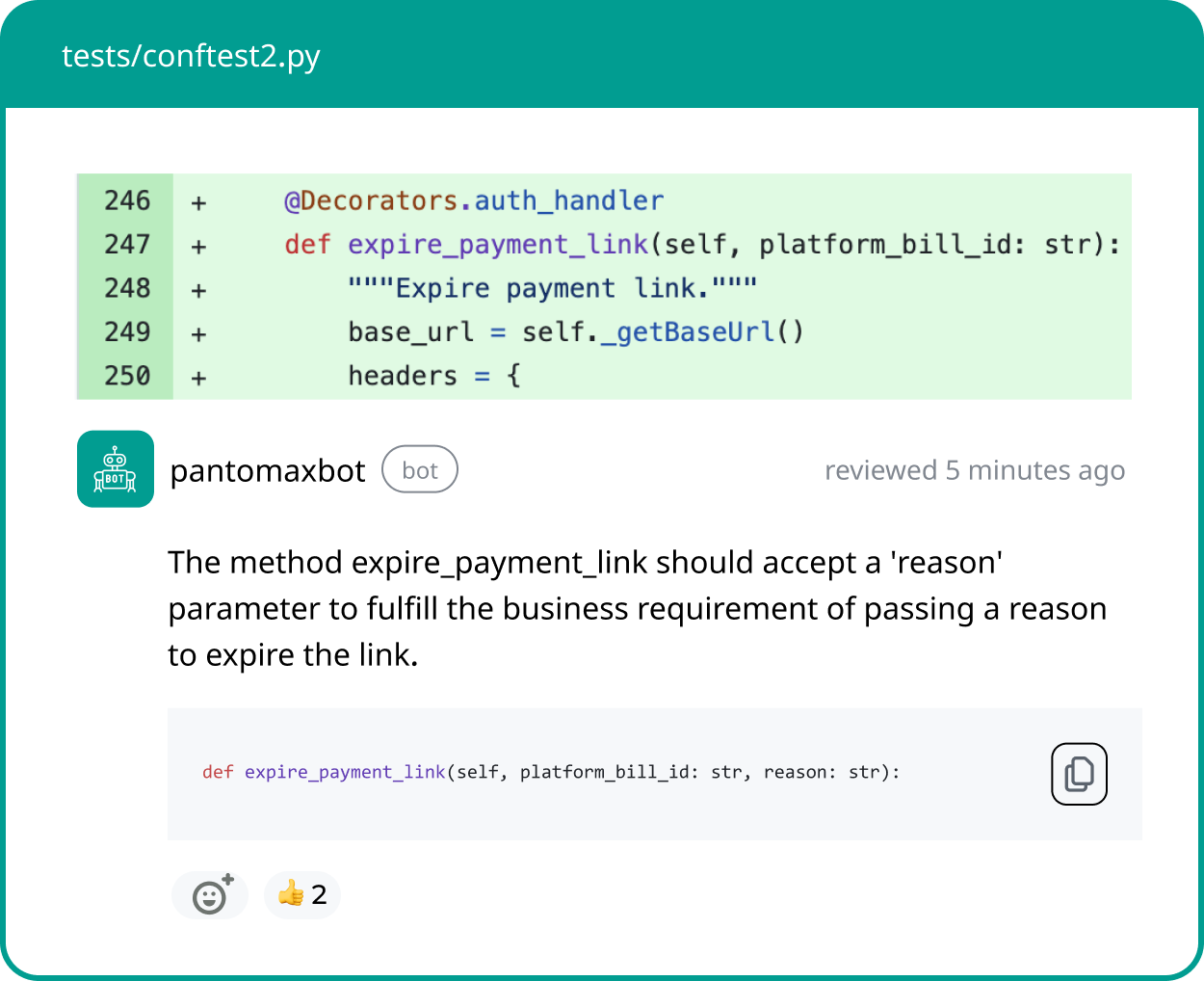

The new model has to be guided:

- Pull attention to the risky parts.

- Summarise intent in plain English, so reviewers don’t waste time reconstructing it.

- Make missing rollout/rollback info uncomfortable.

- Help reviewers build a mental model quickly – then spend human judgement where it matters.

This is not about replacing humans.

It’s little about respecting human limits.

Why I’m writing this (and where we fit)

We’ve built a PR code review tool – yes, in the CodeRabbit category but we started because we were seeing this exact drift.

I’m not interested in “faster reviews” as a pitch. Faster code reviews are easy. You can always go faster by caring less.

I’m interested in code reviews that still do their job in a world where code is cheap and attention is expensive.

If you’re a reviewer and you’ve felt that quiet shift – where you approve things you don’t fully understand because it’s the only way to keep up – you’re not broken. The system is just outdated.

And if you’ve already solved this in your team, I genuinely want to learn how. No posturing.

Because I don’t think this is a tooling problem alone. It’s a workflow + incentives + tooling problem.

But we can at least start by naming it.